Global Point of Care

can high-quality sepsis care and cost consciousness coexist?

There are many factors to consider when diagnosing and treating sepsis – but for the emergency physicians on the front lines, cost usually isn’t one of them. The problem is - it needs to be. Overtreatment, combined with a relatively meager diagnosis-related group (DRG) reimbursement for sepsis, means hospitals often come out on the losing end of the ledger.

"We probably do lose money on sepsis cases,"

says Faheem Guirgis, MD, an emergency medical physician and research fellowship director at UF Jacksonville. “But because we are being held to the standards set by CMS, we have no choice.” In today’s resource-strained environment, this adds tremendous additional strain, and is therefore imperative to address. In this article – the second of a four-part series designed to help you elevate sepsis management – a few of the nation’s top sepsis physicians discuss the biggest problems standing in the way of sustainable sepsis care.

PROBLEM #1

cost isn't often a consideration, because doctors aren't trained on it

Because physicians don’t receive much – if any – financial training, they don’t always feel compelled to consider the dollars and cents.

“Quite frankly, we don’t go to med school thinking, ‘How can I save costs?’ says Dr. Murtaza Akhter. “There is very little education on that, and maybe that’s for good reason – because you don’t want to bias people based on financial issues. That’s not our job. We aren't there to be accountants."

“We try to provide the best care we can,” Dr. Akhter continues. “If it’s expensive, it’s expensive and if it’s cheap, it’s cheap.”

PROBLEM #3

some doctors don't realize that hospitals are bleeding money on sepsis cases

Many physicians are not aware of the dire financial situation surrounding sepsis care. Some assume that most sepsis cases are profitable, but the reality is, hospitals often lose money on them – especially if a patient is admitted for an extended stay.

"If all we do is break even, it's not a good model. With the DRG of sepsis, you’d have to see a couple patients really quickly – where you just have them in the hospital for a day or so – to make up for the overwhelming amount that are in the hospital a couple days,” says Frank LoVecchio, DO, the Director of Research at the University of Arizona Maricopa Medical Center and a longtime emergency department physician. “And you can’t even break even.”

PROBLEM #2

other departments are allowed to spend freely, which sets a double-standard

Although it’s not usually part of their formal training, there is some on-the-job discussion about cost when it comes to treating sepsis in the ER.

“There are people who do get concerned about resources and overutilization of resources,” Dr. Akhter says. But being under the financial microscope can feel frustrating – especially when other doctors and departments are given more financial leeway.

“As uneducated as we are about costs, part of me is like, ‘Why should we be?’” asks Dr. Akhter. “Just look at what the neurosurgeon is doing in the operating room. If you’re a neurosurgeon or an orthopedic surgeon, you can spend as much money as you want because the amount you bring in is so high.”

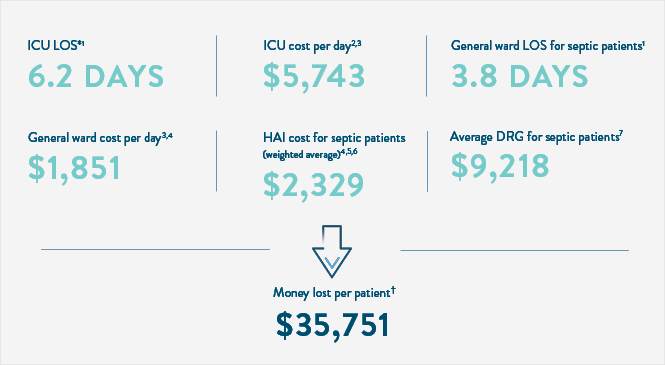

the average cost of sepsis, per patient:

PROBLEM #4:

“checklist medicine” contributes to increased spending

CMS measures and Surviving Sepsis guidelines dictate a specific course of treatment for sepsis, and doctors are often evaluated based on how well they adhere to it. That means physicians sometimes practice “checklist medicine,” as Dr. LoVecchio calls it – where they do what’s right for the metrics, versus what’s right for the patient.

“All you wanted to do is check that CMS box, which is not really driven by the best data,” Dr. LoVecchio says. And checking those CMS boxes can accrue additional costs.

“I don’t want to get all these emails saying I didn’t do things correctly,” says Dr. Guirgis. “That drives a lot of decisions, and that’s why we don’t think about cost so much.”

Physicians also don’t want to skip any steps – even if their gut tells them those steps may be unnecessary in some cases – because it could leave them vulnerable from a legal standpoint. That also means spending more on potentially unnecessary care, just to cover their bases.

“We are scared because of CMS, and scared of legal ramifications,” Dr. LoVecchio says. “We’re just like, ‘Well, so what if they go to the ICU? It’s better than a lawsuit if we miss sepsis.’ I think if you didn’t worry about the CMS and didn’t worry about legal issues, I think we would be more apt to be a little bit more cost conscious.”

PROBLEM #5:

doctors don’t have access to costs to help guide clinical decisions

There are doctors who do consider costs, but there’s plenty of room for improvement.

“We try to educate around costs. I know I personally try to,” Dr. LoVecchio says. “But if you asked me how much does a CBC cost, or how much does a lactate cost at my hospital, I have no idea. No idea. And we’re at fault for that.”

Health systems and doctors should work together to make costs more transparent, Dr. LoVecchio suggests.

“I think that if you order a test, it should show potential charges next to it,” he says.

Doctors are never going to put patients at risk just to save a few dollars, but if two courses of action are likely to yield an equally favorable result, why not go with the cheaper option?

“’Should I be giving this antibiotic or that antibiotic?’ for example,” Dr. Akhter says. “If outcomes are similar, which is cheaper?”

Those types of decisions can extend to nearly every aspect of a patient’s care.

“Being cost conscious would be important with regard to the treatments, the bed utilization, the risk of super infections by giving a few doses of an antibiotic that they don’t need, and the risk of missing what is truly wrong with the patient,” says Dr. LoVecchio.

one thing doctors agree on

All our experts shared the same sentiment: The health of the patient always comes first.

"We are there to treat the patient and not consider the cost,” says Murtaza Akhter, MD, an emergency physician at the University of Arizona. “The cost is a down-the-line issue, but the patient dying is right in front of me. I need to do what it takes to save this guy.”

“I want to do the best I can for my patient,” Dr. Guirgis agrees. “The cost becomes secondary.” The well-being of the individual is paramount, but health systems also need to consider the bigger picture of care delivery. Without a sustainable financial model in place to support proper care for every patient, sepsis care will not be viable for much longer.

shaping the futre of sepsis care

Trying to check off the boxes of best practices while also juggling costs can be incredibly difficult. But identifying the systemic problems holding back sustainable sepsis care is the first step to rectifying them.

It’s clear that both physicians and health systems need to do better – and work together – to find a way to balance quality care with sustainable financial performance.

As we await future assay innovations, the next article in our sepsis management series takes a closer look at three ways today’s top physicians are driving sustainable, high-quality sepsis care already.

References

* Based on the average LOS for severe sepsis, the most common sepsis DRG (comprising 70% of all sepsis cases)

† $44,969 weighted average cost for each septic patient, minus $9,218 weighted average DRG per septic patient

- Ojito JW et al. J Extra Corpor Technol 2012;44:15-20

- Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010 Jan;38(1):65-71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.CCM.0000000000003342.

- Hassan M, Tuckman HP, Patrick RH, Kountz DS, Kohn JL. (2010). Hospital length of stay and probability of acquiring

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2018 National Medicare-Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG), Principal: #870 Septicemia or severe sepsis w mv 96+ hours, #871 Septicemia or severe sepsis w/o mv 96+ hours w mcc, #872 Septicemia or severe sepsis w/o mv 96+ hours w/o mcc. https://tinyurl.com/2p8e5bp9 Accessed 12/21/21.

- Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical Care Medicine Beds, Use, Occupancy, and Costs in the United States: A Methodological Review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(11):2452-2459. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001227.

- Van Vught LA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Spitoni C, et al. MARS Consortium. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Attributable Mortality of Secondary Infections in the Intensive Care Unit After Admission for Sepsis. JAMA. 2016 Apr 12;315(14):1469- 79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2691.

- Wang HE, Jones AR, Donnelly JP. (2017). Revised national estimates of emergency department visits for sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med, 45(9),1443-1449.