View this video about the role of GFAP and UCH-LQ in assessing mTBI.

Global point of care

Global point of care

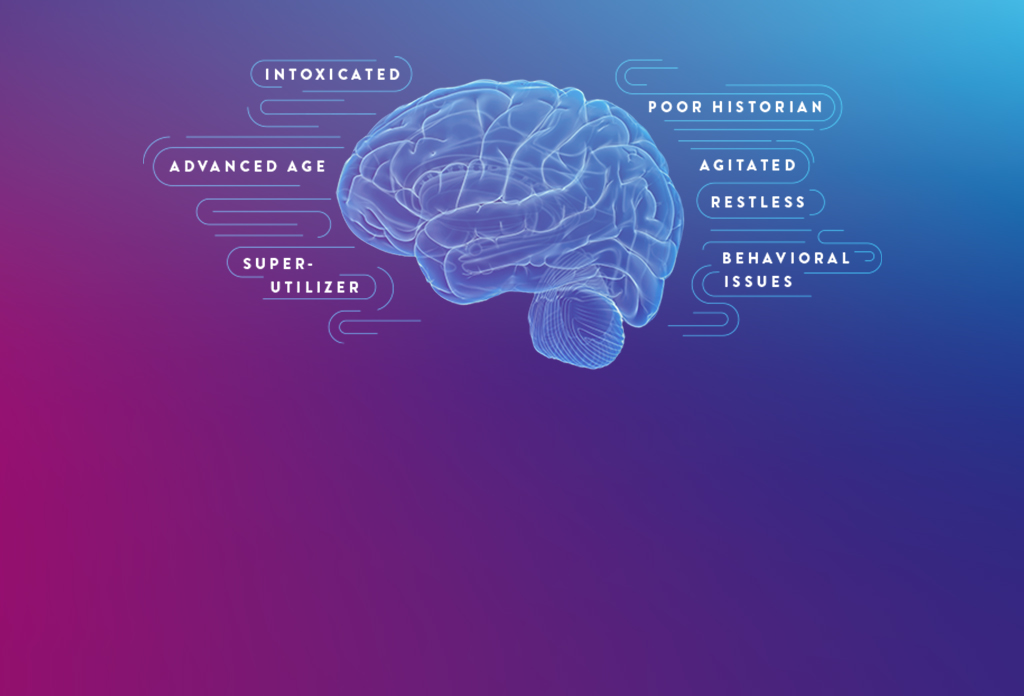

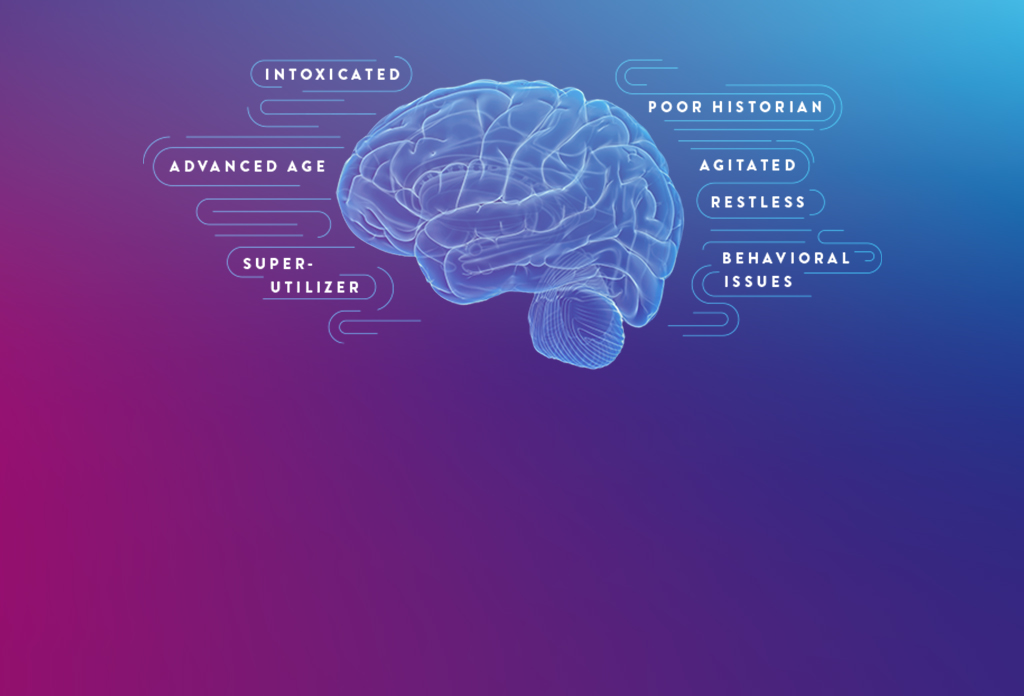

Millions of patients undergo emergency department (ED) evaluation for mTBI each year. Neurocognitive assessments, such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and clinical decision rules (CDRs), are subjective and can be difficult to perform with certain patients, such as those who are intoxicated or have an altered mental health status.¹

As a result, you may decide to order a CT, despite having low clinical suspicion of intracranial bleeding. In fact, while an estimated 82% of patients with TBI undergo CT, more than 90% show no evidence of traumatic abnormality.² What’s more, some patients may insist on a CT even though you deem it unwarranted.

The i-STAT TBI Plasma test may be the solution to provide objective data without time-consuming and often avoidable head CTs for mTBI.

A leader in rapid point-of-care diagnostics.

©2024 Abbott. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, all product and service names appearing in this Internet site are trademarks owned by or licensed to Abbott, its subsidiaries or affiliates. No use of any Abbott trademark, trade name, or trade dress in this site may be made without the prior written authorization of Abbott, except to identify the product or services of the company.

This website is governed by applicable U.S. laws and governmental regulations. The products and information contained herewith may not be accessible in all countries, and Abbott takes no responsibility for such information which may not comply with local country legal process, regulation, registration and usage.

Your use of this website and the information contained herein is subject to our Website Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy: US Citizens | Non-US Citizens. Photos displayed are for illustrative purposes only. Any person depicted in such photographs is a model. GDPR Statement

Not all products are available in all regions. Check with your local representative for availability in specific markets. For in vitro diagnostic use only. For i-STAT test cartridge information and intended use, refer to individual product pages or the cartridge information (CTI/IFU) in the i-STAT Support area.

Abbott - A Leader in Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostics.